Internet Time KnowledgeBase:

Internet Time KnowledgeBase:

Community

Building community is like gardening: you plant the seeds and pray something worthwhile happens. Fertilizer helps. Care is indispensable. But you can't force them to grow. Informal Learning -- the Other 80% Connections: The Impact of Schooling Who Knows?

Collaboration Supercharges Performance (presentation) Trends in Collaborative Learning (Macromedia Breeze) Silicon Valley, The DNA of a Community of Practice

Online Community Technologies and Concepts by Cameron Barrett

reputation management content management mail list management document management categorization collaborative filtering

Robin Good is Mr. Online Collaboration. He spends more than half his time online and probably knows more about online collaboration tools than anyone else on the planet. The Robin Good/Robin Hood connection is apt, for he shares lots of information on his sites: Kolabora and Master New Media.

Robin Good is Mr. Online Collaboration. He spends more than half his time online and probably knows more about online collaboration tools than anyone else on the planet. The Robin Good/Robin Hood connection is apt, for he shares lots of information on his sites: Kolabora and Master New Media.

Robin Good kicks off Competitive Edge. We are there.

A Manifesto for Collaborative Tools by Eugene Eric Kim

Internet Time Group on building community (dated)

Beyond One-to-One: The Power of Purposeful Communities, ArsDigita Building an Online Community (book), ArsDigita

Learnativity on Building Community

Nine Timeless Design Strategies for Community Building

(Amy Jo Kim)

Doblin Group's community bibliography

Joel Udell's Internet Groupware for Scientific Collaboration is a comprehensive guide to software for coordinating events, discussing issues, publishing findings, and making & distributing news.

These Sites Make Teams Work, Fast Company's comparison of five Web-based tools that are designed to help teams work better.

Distributed Learning Communities, CU Denver The Nature of Nets, Doblin Group Collaborative Strategies -- great case studies and astute analysis by SF consulting firm. groupware gurus.

Cafe Knowhow from The World Cafe (Juanita Brown) Howard Rheingold handpaints his shoes, here's his Virtual Community group jazz hosts events Electronic Learning Communities Research Group at Georgia Tech. (Amy Bruckman) Online Discussion Groups

Resources for Moderators and Facilitators of Online Discussion (Collins and Berge)

Yet, there are times when people need to see each other face-to-face for optimal learning. What are these?

Teambuilding—True teambuilding means being together—at the same place. Building trust, a sense of purpose, and commitment to outcomes requires an intimacy not possible through technology at this time.

Personal coaching—Feedback and coaching around performance issues is difficult, if not impossible, if the climate of trust and respect hasn’t been built in real-time, face-to-face.

Networking/Teaming—Getting a sense of an individual, exchanging thoughts and ideas, and crafting the invisible links that tie a network together require engaging the senses in the interaction.

Building culture—Organizational culture is built on a shared commitment to values. The shaping of these values to inspire and motivate performance need multiple face-to-face contacts with all involved—thinking, doing, acting, and reacting to embed the cultural values in each person.

The Invisible Key to Success, Fortune, Tom Stewart (1996)

Denham Grey's Knowledge Community has a great and growing selection of links on communities of practice, who's doing what, and who the players are. See also his Collaboration Tools (How can you have community without collaboration?)

Convergence is coming....

On-line Collaborative Learning Environments, a special issue of Journal of International Forum of Educational Technology & Society

Is "virtual community" just a Ponzi scheme?

Participating on The WeLL taught me more about community than anything since.

They have a deal (until 3/31/01) where you can try it out for $2. Use me as your reference (jaycross@well.com).The WeLL was acquired. The only way I could maintain my email address and access was to purchase Salon Premium. Good bye, old friend.

Community Building on the Web : Secret Strategies for Successful Online Communities by Amy Jo Kim. ISBN: 0201874849 . $29.99. Check out the companion web site.

Don't leave out the fun.

The Social Life of Information

by John Seely Brown and Paul Duguit (2000).

Well-written argument that ontent is not king. The refuge of simplistic infocentric futurists: demassification, decentralization, denationalization, despacialization, disintermediation, and disaggregation.

Jay's notes on The Social Life

Communities of Practice: The Organizational Frontier

Harvard Business Reivew, 1/1/00 by Etienne C. Wenger & William M. Snyder

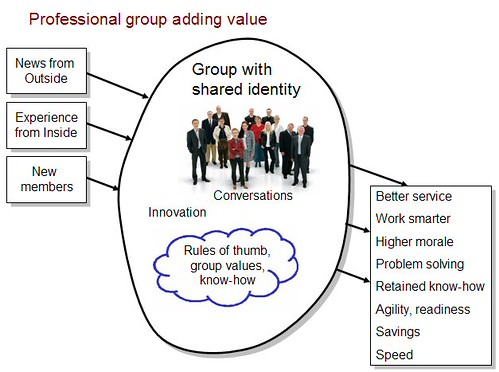

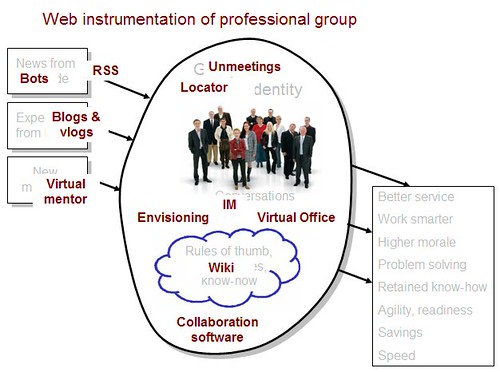

A new organizational form is emerging in companies that run on knowledge: the community of practice. And for this expanding universe of companies, communities of practice promise to radically galvanize knowledge sharing, learning, and change. A community of practice is a group of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise.

Communities of practice can drive strategy, generate new lines of business, solve problems, promote the spread of best practices, develop people's skills, and help companies recruit and retain talent. The paradox of such communities is that although they are self-organizing and thus resistant to supervision and interference, they do require specific managerial efforts to develop them and integrate them into an organization.

Fred Nichols on Communities of Practice (2000)

Nurturing Three Dimensional Communities of Practice: How to get the most out of human networks, Knowledge Management Review, Richard McDermott, PhD (1999)

Key Hypotheses in Supporting Communities of Practice by John Sharp (1997)

In February 2004, I finally got an opportunity to hear Etienne Wenger in person and spend a little time chatting with him.

Etienne Wenger is a social learning theorist who cut his teeth at the Institute for Research on Learning. He is best known for popularizing the concept of communities of practice. His presentation spoke to me deeply.

Communities of practice are not new. The earliest version may have been cavemen sitting around a fire talking about the best way to hunt bears. That’s the way “communities” work: practitioners in a field or practice come together to share, nurture, and validate tricks of the trade. Apprentices have always done this. Sometimes we mistakenly thought most of the learning was going on between master and apprentice. In fact, most apprentices probably learn more from one another.

Question: What does a flower know about being a flower? And what does a computer know about being a flower? Stumped? That’s because neither flowers nor computers are members of the human community, and it’s community that harbors knowledge.

A friend of Etienne is a wine professional. Describing a wine, the friend said it was “purple in the nose.” This meant absolutely nothing to Etienne, because he is not a member of the wine-tasting community.

Now imagine the wine-tasting friend is with his fellow wine tasters. He discerns a new element in the wine which he describes as a convergence of fire and gravity. If others in the group buy in, the fire & gravity meme is legitimized. Here we have the two primary aspects of any community: participation and reification.

By the way, the concept of community is value-neutral. The word community has a warm and fuzzy feel to it, but we’re talking about groups that can impede progress, engage in group think, or neglect their responsibilities to the larger organization. I recall being shut out of a community of instructional designers because I was perceived as a business man, not a designer.

Now let’s think about how eLearning might be a transformative force. Learning in a community involves answering four questions:

• Identity: Who are we becoming? • Meaning: What is our experience? • Practice: What are we doing? • Community: Where do we belong?

Learning by sharing knowledge in a community leads to what Etienne calls the “horizontalization” of learning. In school or workshops, the learning relationship is vertical: there’s a provider on top and a recipient. In a horizontal community, peers learn from one another.

First generation knowledge management failed because it was top down. (Identify the critical knowledge and stuff it in a content management system. Nobody took ownership because no community embodied the knowledge. Now that we appreciate that knowledge lives in communities, we can facilitate KM by nurturing their development. Etienne quotes Pasteur, saying “Chance favors those who are prepared.”

Etienne suggests scrapping our industrial model of training and the notions that go with it. Learning will become an internal part of live itself. Teaching will fade in importance. Progress along a trajectory of development will replace skills training.

The three aspects of social learning are the Domain, the Practice, and the Community. What, how, and who.

Related links: What is Knowledge, Building Community, and Informal Learning.

Googling out these references to past entries here, I found that I'd already recorded many of the concepts Etienne presented in Edinburgh. No matter. It took an hour of live presentation for them to take hold in a transformative way.

Peter Senge: "Knowledge generation really only occurs in teams, where people engage in doing meaningful work." Teams are task-oriented and fleeting; they don't last. As the teams dissolve, people go off and reform in other teams. But they keep those networks of relationships, and they maintain those community ties." The Fifth Discipline... "was really about team learning and not very much about organizational learning. It took all our experience with member companies to recognize that communities are the place where this knowledge moves into, gets tapped, accessed, diffused and shared. Knowledge is contextual; it comes in the context of doing work. We send people off to training, we educate them, we give them tools and ideas. But that's not really knowledge generation. The real question is what happens when people try to use their training?"

Learning Organization (but read the above)

Peter Henschel, in LiNEzine

The manager’s core work in this new economy is to create and support a work environment that nurtures continuous learning. Doing this well moves us closer to having an advantage in the never-ending search for talent.

By sheer force of habit, we often substitute training for real learning. Managers often think training leads to learning or, worse, that training is learning. But people do not really learn with classroom models of training that happen episodically. These models are only part of the picture. Asking for more training is definitely not enough—it isn’t even close. Seeing the answer as “more training” often obscures what’s really needed: lifelong, continuous learning in work and at work.

That is one reason why preserving the integrity of these informal communities is so important. The worst effects of downsizing and reengineering come from their complete disregard for communities of practice. The fact that training deals only with explicit knowledge, while the value is often in tacit knowledge, is another reason training can get at only part of what is understood to be effective. The other main limitation of traditional classroom training is that it is episodic and mostly relies on “push” (we want you to know this now) rather than “pull” (I need to know this now and am ready to learn it).

Another dimension to the community idea is seldom discussed, but critically important: Learning is powerfully driven by the critical link between learning and identity. We most often learn with and through others.

What we choose to learn depends on:

- Who we are

- Who we want to become

- Which communities we wish to join or remain part of.

So, not wanting to be like “them” can be enough to keep someone from learning. That fact seems to hold whether we are talking about company apprentices, high school gangs, or seasoned software engineers.

But it gets even more interesting: IRL studies, among others, have shown that as much as 70% of all organizational learning is informal. Everyday, informal learning is constant and everywhere. If this insight is true even in a bare majority of enterprises, why would we leave so much learning to sheer chance?

Slashdot Posted by JonKatz on Tuesday October 03, @12:00PM

from the de-bunking-the-utopians dept. Berkeley scholar Joseph Lockard (a doctoral candidate in English Literature) claims the idea of the virtual community is a Ponzi scheme, promoted by benighted utopians and elitists who equate access to the Net and the Web with social and democratic enlightenment. This myth has been virtually unchallenged for years, he says, and in a provocative and interesting essay called Progressive Politics, Electronic Individualism, and the Myth of Virtual Community, Lockard claims that it's nothing more than a bunch of hooey. Does anybody out there think virtual communities are real?

Lockard's essay scores more than once. He's right in going after the hype that has surrounded the idea of the virtual community for years now. The tech world is rich and elitist, and becomes more so daily. Apart from developments like open source, which has done much to try and make technology more inclusive (though very few people will ever be able to successfully program) there are few signs yet that the Net is re-vitalizing democracy, or that virtual communities are supplanting or improving upon real ones. online, we see little organized concern for the technologically-deprived, or worry about the inevitable social divisions created by classes of empowered and tech-deprived people. It's already obvious that people with access to computing and the Net will have enormous educational, social and business advantages over those who don't; the latter face menial, low-paying jobs all over the planet.

Lockard also accurately points out that the largest communities forming online are corporate, not individualistic, and their agenda is marketing, not community. He calls the very idea of a "virtual community" an oxymoron.

"Instead of real communities, cyber-communities sit in front of the [late but not lamented] Apple World opening screen that pictures a cluster of cartoon buildings which represent community functions (click on post office for e-mail, a store for online shopping, a pillared library for electronic encyclopedias, etc.)" Such software addresses only a desire for community, Lockard writes, not the real thing.

...Certainly there are bulletin boards and mailing lists -- from sex sites to San Francisco's WELL, from media-centric gatherings from pet rescue forums to AOL's Senior Net -- that have functioned for some time as very real communities that foster conversation and mutual understanding, spawn friendships, generate support for members in trouble. Topical, community oriented Websites -- everything from Camworld.com, Kuro5shin and myvideogames.com to Slashdot -- function as information or true cultural communities as well -- sometimes for idea-sharing, sometimes for material support and information.

The early cyber-gurus definitely got carried away by notions that everything would become virtual, a mistake now shared by all sorts of panicked businesses -- publishing comes to mind -- and starry-eyed utopians. Cyberspace is definitely a new kind of space, but there's as yet no reason to believe that it won't compliment or co-exist with the material kind. So far at least, virtual communities suggest a Middle Kingdom, existing somewhere in the middle between the utopian fantasies and Lockard's dismissive jeers.

Online people do make powerful connections and the virtual realm does permit us to share information (including software), research and commerce and and encounter all sorts of people in all kinds of places -- something that has never been possible before. But when the dust settles, and if the history of technology offers any clues, people will always hang out with their friends, get drunk. They'll still be logging off their computers to have sex, get married, fight with their parents, send their kids off to school and go to the movies, and seek out the company of human beings to meet human needs. The best virtual communities have always complimented that need, not supplanted it.

Corporate Culture in Internet Time

By Art Kleiner

Anyone who has tried to create a culture knows it can't be done on Internet time. Cultures aren't designed. They simmer; they fester; they brew continually, evolving their particular temperament as people learn what kind of behavior works or doesn't work in the particular company. The most critical factor in building a culture is the behavior of corporate leaders, who set examples for everyone else (by what they do, not what they say). From this perspective, the core problem faced by most e-commerce companies is not a lack of culture; it's too much culture. They already have two significant cultures at play - one of hype and one of craft.

...during most of the 20th century, as companies matured into mainstream corporations, other cultures - those of finance, labor relations, marketing and managerial bureaucracy - eclipsed and overwhelmed the cultures of hype and craft.

It is currently fashionable to say that the old, tightly knit mentoring relationships of bricks-and-mortar companies are dead, that individuals are now responsible for their own development and career growth. Unfortunately, this view is not sustainable; there are too many risks, even in a high-growth economy, and too much human waste. The task of developing people will move away from companies, since they are not stable enough; it will move to the team level. In other words, if success depends on building a new "culture," that effort will have a lot more effect at the team level than on any company-wide level. It's reasonable to expect, in the turbulent e-commerce business environment, that companies won't necessarily evolve intact cultures. But teams do; as one e-commerce veteran puts it, they're "islands of stability in a place where nothing else is stable."

Ultimately, I suggested to Jane, all the organizational-learning techniques in the world wouldn't do her any good unless she were willing to go to her bosses, the startup's founders, and say something like this:

It is this discussion that has captured the categories we use to analyze the social impact of the Internet. The Internet has been drafted to serve duty as yet more evidence of the disintegration of "community", etc. As is sadly always the case in American intellectual discourse, complex social and historical issues get reduced as quickly as possible to simplistic binary oppositions which exclude by definition all the really interesting choices and developments (a good analogy here is our reduction of the categories used to analyze sexual behavior to either promiscuity or monogamy)."If you let me build my own team, and choose and develop the people, I'm willing to take on [name of tough, challenging project here]. But I want to take our own development seriously. I want to try some new ways of organizing the work, regularly evaluate them, and try to learn how to manage ourselves in this new territory. After a few months, we'll come back together and see what we've accomplished, and which of those innovations might apply to the other teams around here. But it will only work if you give our team enough autonomy to learn from our experiments."

12 Principles for Designing an Online Gaming Community

Define the community's purpose

Create distinct gathering spaces

Provide rich communications

Implement a rankings ladder

Evolve member profiles over time

Provide online hosting and support

Offer guidance to new members

Provide a growth path

Support member-created subgroups

Anticipate disputes

Hold regularly scheduled events

Acknowledge the passing of time

It's Not What You Know, It's Who You Know

Work in the Information Age First Monday, 5/2000 http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue5_5/nardi/index.html#n1

"It's not what you know, but who you know," could, paradoxically, be the motto for the Information Age. We discuss the emergence of personal social networks as the main form of social organization in the workplace.

NetWORK is our term for the work of establishing and managing personal relationships. These relationships can involve a rich variety of people including customers, clients, colleagues, vendors, outsourced service providers, venture capitalists, alliance partners in other companies, strategic peers, experts such as legal and human relations staff, and contractors, consultants, and temporary workers. These are fundamental business relationships in today's economy. As we have noted, studies that focus on narrowly scoped "teams" miss the vital work that goes into relationships that enmesh workers in a much wider, more complex social framework.

To keep their network engines revved, workers constantly attend to three tasks:

- Building a network: Adding new nodes (people) to the network so that there are available resources when it is time to conduct joint work;

- Maintaining the network, where a central task is keeping in touch with extant nodes;

- Activating selected nodes at the time the work is to be done.

NetWORK is an ongoing process of keeping a personal network in good repair. In the words of one study participant, "Relationships are managed and fed over time, much as plants are."

The reduction of corporate infrastructure means that instead of reliance on an organizational backbone to access resources via fixed roles, today's workers increasingly access resources through personal relationships. Rather than being embraced by and inducted into "communities of practice," workers meticulously build up personal networks, one contact at a time. Accounts of the "virtual" organization and organizations with flattened hierarchies have stressed the benefits of the streamlined, nimble, democratic workplace, responsive to contingency, empowering workers to make decisions quickly and independently. It seems however, that these transformed organizations also mean reduced institutional support, and that individual workers incur some of the costs associated with these corporate gains. In the Information Age, workers meet the challenges of diminishing organizational resources through who they know.

I do not believe the internet is an effective facilitator of community. And this fact is largely irrelevant to how we judge its impact on society. Instead, what the internet facilitates is friendship, and it does this in a very 19th century way - through writing. The modern replacement for traditional community is a web of self-chosen relations that can now span the globe. In this respect we are recreating the relations that existed among scholars and humanists in Europe before the modern era, except that now it is no longer just the elite that have this opportunity.

The development of friendship in this manner is I believe a very good alternative to traditional community, which, for all the "meaning" it bestows on life, is more often than not coercive, intolerant and closed-off. I see the disappearance of the one and the ascent of the other as a good thing, not something to lament. (Most of the intellectuals today whining about community would never put up with one in reality for a second, since they would never assent to the restrictions on their personal freedom that communities traditional require).

Participation Inequality

from Jakob Nielsen

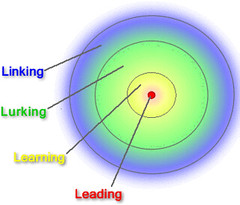

A major reason why user-contributed content rarely turns into a true community is that all aspects of Internet use are characterized by severe participation inequality (a term I have from Will Hill of AT&T Laboratories). A few users contribute the overwhelming majority of the content, while most users either post very rarely or not at all. Unfortunately, those people who have nothing better to do than post on the Internet all day long are rarely the ones who have the most insights. In other words, it is inherent in the nature of the Internet that any unedited stream of user-contributed content will be dominated by uninteresting material.

The key problem is the unedited nature of most user-contributed content. Any useful postings drown in the mass of "me too" and flame wars. The obvious solution is to introduce editing, filtering, or other ways of prioritizing user-contributed content. One idea is to pick a few of the best reader comments and make them prominent by posting them directly on the primary page, while other reader comments languish on a secondary page. It is also possible to promote the most interesting postings based on a vote by other readers who could click "good stuff" or "bozo" buttons.

Collaboration is a lot more than communication and will eventually split off into a separate topic.

|

Culture |

Value discipline |

Where it shines |

Source of shareholder value |

Global focus |

End stage |

|

Cultivation |

Discontinuous innovation |

Early market |

Infectious charisma |

Shared vision |

Cult |

|

Competition |

Product leadership |

Early, bowling alley, tornado |

Pierce competitiveness |

Measurement & compensation |

Caste systems |

|

Control |

Operational excellence |

Tornado, Main Street |

Relentless improvement |

Business Planning |

Bureaucracy |

|

Collaboration |

Customer intimacy |

Bowling alley, Main Street |

Perceptive adaptation |

Customer focus |

Club |

From Clock of the Long Now

From Clock of the Long Now

The Learning HIstory Project is a combination of story telling and corporate culture. Very much in tune with the work we did at Oral History Associates.

An Utne Reader Guide to Conducting Salons, Council and Study Circles —By Eric Utne

Throughout this guide the word salon is used to describe a wide range of ways groups can interact.

* Traditional salons like those that seeded the French Revolution tend to emphasize spirited group discussion. * Council, derived mainly from Native American traditions, emphasizes "devout listening" and unpremeditated speaking. * Study circles tend to involve reading and focused group discussion.

www.downes.ca/cgi-bin/website/view.cgi?dbs=Article&key=1075564356

About Corporation for Positive Change

Corporation for Positive Change (CPC) is dedicated to the design and development of Appreciative organizations - those capable of sustaining innovation, financial well-being and market leadership by inspiring the best in human beings. CPC provides consultation and training based on the principles and practices of Appreciative Inquiry. For more information about CPC, or to contact any of our principal consultants, please visit our web site at www.positivechange.org.

David Bohm on Dialogue

The e-Discussion Toolkit, suggestions for setting up and implementing online problem-solving discussions. "Since 1998 electronic discussions have played a valuable role at the World Bank. By promoting consultations with the public, they have furthered the vision of the Knowledge Bank, which is about putting in place systems for capturing knowledge more effectively.""

The Salon-Keeper's Companion